in order to compare and contrast leadership perspectives across the globe what constructs were used

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Priorities and challenges for health leadership and workforce management globally: a rapid review

BMC Wellness Services Research volume 19, Commodity number:239 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Health systems are complex and continually changing beyond a diverseness of contexts and wellness service levels. The capacities needed by health managers and leaders to answer to current and emerging issues are not yet well understood. Studies to appointment take been country-specific and have not integrated unlike international and multi-level insights. This review examines the current and emerging challenges for health leadership and workforce management in diverse contexts and health systems at three structural levels, from the overarching macro (international, national) context to the meso context of organisations through to the micro context of individual healthcare managers.

Methods

A rapid review of evidence was undertaken using a systematic search of a selected segment of the diverse literature related to health leadership and management. A range of text words, synonyms and subject headings were developed for the major concepts of global wellness, wellness service management and health leadership. An explorative review of three electronic databases (MEDLINE®, Pubmed and Scopus) was undertaken to identify the key publication outlets for relevant content betwixt January 2010 to July 2018. A search strategy was then practical to the key journals identified, in addition to hand searching the journals and reference list of relevant papers identified. Inclusion criteria were independently applied to potentially relevant manufactures by three reviewers. Data were field of study to a narrative synthesis to highlight central concepts identified.

Results

Sixty-3 articles were included. A set up of consequent challenges and emerging trends within healthcare sectors internationally for wellness leadership and direction were represented at the iii structural levels. At the macro level these included societal, demographic, historical and cultural factors; at the meso level, human being resource management challenges, changing structures and performance measures and intensified direction; and at the micro level shifting roles and expectations in the workplace for health care managers.

Conclusion

Contemporary challenges and emerging needs of the global health management workforce orient around efficiency-saving, modify and human resource management. The role of health managers is evolving and expanding to meet these new priorities. Ensuring contemporary health leaders and managers have the capabilities to respond to the current mural is critical.

Background

Health systems are increasingly complex; encompassing the provision of public and private health services, primary healthcare, acute, chronic and aged intendance, in a variety of contexts. Health systems are continually evolving to accommodate to epidemiological, demographic and societal shifts. Emerging technologies and political, economic, social, and environmental realities create a complex agenda for global health [1]. In response, there has been increased recognition of the office of non-country actors to manage population needs and bulldoze innovation. The concept of 'collaborative governance,' in which not-wellness actors and health actors work together, has come up to underpin health systems and service delivery internationally [1] in gild to meet irresolute expectations and new priorities. Seeking the achievement of universal health coverage (UHC) and the Sustainable Evolution Goals (SDGs), specially in low- and middle-income countries, have been pivotal driving forces [two]. Agendas for change have been encapsulated in reforms intended to improve the efficiency, disinterestedness of admission, and the quality of public services more broadly [1, 3].

The profound shortage of human resource for health to address current and emerging population wellness needs across the earth was identified in the World Wellness Organization (WHO) landmark publication 'Working together for health' and continues to impede progress towards the SDGs [4]. Despite some improvements overall in health workforce aggregates globally, the man resource for health challenges against wellness systems are highly complex and varied. These include not merely numerical workforce shortages just imbalances in skill mix, geographical maldistribution, difficulty in inter-professional collaboration, inefficient use of resource, and burnout [2, 5, half dozen]. Effective health leadership and workforce management is therefore critical to addressing the needs of homo resources within health systems and strengthening capacities at regional and global levels [4, half dozen,7,eight].

While there is no standard definition, health leadership is centred on the power to identify priorities, provide strategic management to multiple actors within the health system, and create delivery across the wellness sector to address those priorities for improved health services [vii, viii]. Constructive management is required to facilitate change and achieve results through ensuring the efficient mobilisation and utilisation of the wellness workforce and other resource [8]. As contemporary health systems operate through networks inside which are ranging levels of responsibilities, they require cooperation and coordination through effective wellness leadership and workforce management to provide loftier quality care that is constructive, efficient, accessible, patient-centred, equitable, and safe [9]. In this regard, health leadership and workforce direction are interlinked and play critical roles in health services management [7, 8].

Along with wellness systems, the role of leaders and managers in health is evolving. Strategic management that is responsive to political, technological, societal and economic change is essential for health system strengthening [x]. Despite the pivotal function of health service management in the health sector, the priorities for health service direction in the global wellness context are not well understood. This rapid review was conducted to place the current challenges and priorities for wellness leadership and workforce direction globally.

Methods

This review utilised a rapid bear witness assessment (REA) methodology structured using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [11]. An REA uses the same methods and principles as a systematic review but makes concessions to the breadth or depth of the process to address key issues well-nigh the topic under investigation [12,13,fourteen]. An REA provides a balanced cess of what is already known well-nigh an consequence, and the strength of evidence. The narrower research focus, relative to full systematic reviews, make REAs helpful for systematically exploring the evidence around a particular issue when there is a broad evidence base of operations to explore [xiv]. In the present review, the search was limited to contemporary literature (post 2010) selected from leading health service management and global health journals identified from exploring major electronic databases.

Search strategy

Phase one

An explorative review of three core databases in the area of public health and health services (MEDLINE®, Pubmed and Scopus) was undertaken to place the primal publication outlets for relevant content. These databases were selected as those that would be nearly relevant to the focus of the review and accept the broadest range of relevant content. A range of text words, synonyms and subject headings were developed for the major constructs: global health, health service direction and health leadership, priorities and challenges. Regarding health service management and health leadership, the following search terms were used: "healthcare manag*" OR "health manag*" OR "health services manag*" OR "wellness leader*". Due to the big volume of diverse literature generated, a systematic search was and so undertaken on the primal journals that produced the largest number of relevant manufactures. The journals were selected equally those identified equally likely to comprise highly relevant cloth based on an initial scoping of the literature.

Phase 2

Based on the initial database search, a systematic search for articles published in English between 1 January 2010 and 31 July 2018 was undertaken of the current bug and archives of the following journals: Asia-Pacific Journal of Wellness Management; BMC Health Services Research; Healthcare Management Review; International Journal of Healthcare Management; International Journal of Wellness Planning and Management; Journal of Healthcare Direction; Periodical of Health Arrangement and Management; and, Journal of Health Management. Hand-searching of reference lists of identified papers were also used to ensure that major relevant material was captured.

Study selection and data extraction

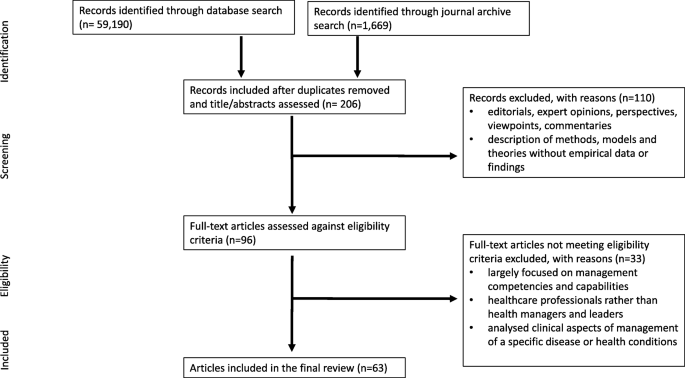

Results were merged using reference-management software (Endnote) and any duplicates removed. The first author (CF) screened the titles and abstracts of manufactures meeting the eligibility criteria (Table 1). Full-text publications were requested for those identified as potentially relevant. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were then independently practical by ii authors. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or consultation with a third person, and the following data were extracted from each publication: author(s), publication year, location, primary focus and principal findings in relation to the research objective. Sixty-three articles were included in the final review. The selection process followed the PRISMA checklist [11] as shown in Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow nautical chart of the literature search, identification, and inclusion for the review

Data extraction and analysis

A narrative synthesis was used to explore the literature confronting the review objective. A narrative synthesis refers to "an approach to the systematic review and synthesis of findings from multiple studies that relies primarily on the utilize of words and text to summarise and explain the findings of the synthesis" [fifteen]. Firstly, an initial description of the primal findings of included studies was drafted. Findings were and then organised, mapped and synthesised to explore patterns in the data.

Results

Search results

A total of 63 manufactures were included; Table ii summarizes the data extraction results by region and state. Nineteen were undertaken in Europe, 16 in North America, and one in Australia, with relatively fewer studies from Asia, the Middle East, and small island developing countries. Eighteen qualitative studies that used interviews and/or focus group studies [xvi,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] were identified. Other studies were quantitative [33,34,35,36,37,38,39] including the use of questionnaires or survey data, or used a mixed-method arroyo [40,41,42,43,44]. Other articles combined different types of principal and secondary data (fundamental informant interviews, observations, focus groups, questionnaire/survey data, and government reports). The included literature also comprised 28 review articles of various types that used mixed information and bibliographic evidence.

Central challenges and emerging trends

A set of challenges and emerging trends were identified beyond healthcare sectors internationally. These were grouped at iii levels: 1) macro, system context (gild, demography, technology, political economy, legal framework, history, culture), 2) meso, organisational context (infrastructure, resources, governance, clinical processes, direction processes, suppliers, patients), and 3) micro context related to the individual healthcare director (Tabular array iii). This multi-levelled approach has been used in previous research to demonstrate the interplay between unlike factors across different levels, and their direct and indirect reciprocal influences on healthcare management policies and practices [45].

Societal and system-wide (macro)

Population growth, ageing populations, and increased illness burdens are some of the mutual trends health systems are facing globally. Developing and adult countries are going through demographic and epidemiological transitions; people are living longer with increasing prevalence of chronic diseases requiring health managers and leaders to adapt to shifting healthcare needs at the population level, delivering preventative and long-term intendance beyond acute care. Countries in Africa, Europe, the Pacific Islands, Center East, Asia and Caribbean area are seeing an increase in number of patients with non-communicable diseases and infectious disease [21, 46,47,48,49,l,51,52].

Although many countries take similar emerging health system concerns, there are some differences in the complexities each country faces. For many modest countries, outmigration, capacity edifice and funding from international aid agencies are affecting how their health systems operate, while in many larger countries, funding cuts, rising in private health insurance, innovations, and wellness organisation restructuring are major influences [21, 34, 50, 53, 54]. In addition, patients are increasingly health literate and, every bit consumers, expect high-quality healthcare [34, 53, 54]. Even so, hospitals and healthcare systems are defective capacity to meet the increased demand [16, 34, 43].

Scientific advances have meant more patients are receiving intendance across the health system. It is imperative to have processes for advice and collaboration between different health professionals for high-quality intendance. However, health systems are fragmented; increasing specialisation is leading to further fragmentation and disassociation [31, 54, 55]. Adoption of technological innovations also require change management, hospital restructure, and capacity building [56,57,58].

Changes in health policies and regulations compound the claiming faced by healthcare managers and leaders to deliver high quality care [53, 54, 59]. Political reforms oftentimes pb to health system restructuring requiring change in the values, structures, processes and systems that can constrain how health managers and leaders marshal their organisations to new agendas [24, 28, 31, 60]. For example, the distribution of wellness services management to local authorities through decentralisation has a variable affect on the efficacy and efficiency of healthcare delivery [24, 27, 35, 59].

Governments' decisions are oft fabricated focusing on cost savings, resulting in budgetary constraints within which wellness systems must operate [16, xix, 53, 61]. Although some wellness systems accept delivered positive results under such constraint [53], often financial resource constraints can lead to poor homo and technical resource resource allotment, creating a disconnect between demand and supply [23, 27, 40, 47, 57]. To reduce spending in astute care, there is also a push to deliver health services in the customs and focus on social determinants of health, though this brings further complexities related to managing multiple stakeholder collaborations [27, 32, 34, 38, twoscore, 49, 55].

Due to an increment in demand and cost constraints, new business models are emerging, and some health systems are resorting to privatisation and corporatisation [22, 48, 62]. This has created contest in the market, increased uptake of private health insurance and increased movement of consumers betwixt various organisations [22, 48]. Health managers and leaders need to keep abreast with continuously irresolute business concern models of care delivery and appraise their bear on [59, 62]. The evolving international health workforce, bereft numbers of trained health personnel, and maintaining and improving advisable skill mixes comprise other of import challenges for managers in coming together population health needs and demands (Table three).

Organisational level (meso)

At the organisation level, human resource management bug were a fundamental business organization. This can be understood in part within the wider global human being resources for wellness crisis which has placed healthcare organisations under intense force per unit area to perform. The bear witness suggests healthcare organisations are evolving to strengthen coordination between main and secondary care; at that place is greater attending to population-based perspectives in disease prevention, interdisciplinary collaboration, and clinical governance. These trends are challenged past the persistence of bureaucratic and hierarchical cultures, emphasis on targets over intendance quality, and the intensification of forepart-line and middle-management work that is limiting capacity.

Healthcare managers and leaders also face up operational inefficiencies in providing principal wellness and referral services to accost highly complex and shifting needs which ofttimes result in the waste product of resource [49, 63, 64]. Considering the step of change, organisations are required to be flexible and deliver higher quality care at lower cost [21, 53, 65]. To reach this, many organisations in developing and adult countries alike are adopting a lean model [17, 21]. However, there are challenges associated with ensuring sustainability of the lean system, adjusting organisational hierarchies, and improving cognition of the lean model, especially in developing countries [17, 21].

Healthcare organisations crave diverse actors with dissimilar capabilities to deliver high quality care. However, a dominant hierarchical civilization and lack of collaborative and distributed culture can limit the operation of healthcare organisations [22, 36, 54]. In addition, considering high turnover of executive leadership, healthcare organisations often rely on external talent for succession management which can reduce hospital efficiency [44, 66]. Other contributors to weakened hospital performance include: the lack of allocative efficiency and transparency [24, 30, 64, 67]; poor infirmary processes that hamper the development of constructive systems for the prevention and control of hospital caused infections (HAIs) [53, 68]; and, payment reforms such as value-based funding and fee-for-service that encourage volume [18, 23, 24, 61, 62, 69, seventy].

Managerial work distribution within organisations is frequently not clearly defined, leading to extra or extreme work conditions for middle and forepart-line managers [29, 42, 53, 70]. Unregulated and undefined expectations at the system level leads to negative effects such every bit stress, reduced productivity, and unpredictable work hours, and long-term effects on organisational efficiency and delivery of high quality care [22, 28, 29, 37, 42, 51, 71]. Furthermore, often times front-line clinicians are also required to take the leadership role in the absence of managers without proper preparation [20]. Despite this, included studies indicate that the involvement of middle and front-line managers in strategic decision-making can exist limited due to diverse reasons including lack of back up from the organisation itself and misalignment of private and organisational goals [xvi, 26, 31, 72].

Individual level (micro)

Worldwide, heart and front-line wellness managers and leaders are unduly afflicted by challenges at the system and organisational level, which has contributed to increasing and often conflicting responsibilities. Some countries are experiencing a growth in senior wellness managers with a clinical groundwork, while in other countries, the antipodal is apparent. Indistinct organisational boundaries, increasing telescopic of practice, and lack of systemic support at policy level are leaving healthcare managers with undefined roles [28, 59]. Poorly defined roles contribute to reduced accountability, transparency, autonomy, and understanding of responsibilities [24, thirty, 31, 67]. Studies besides indicate a lack of recognition of clinical leaders in health organisations and inadequate training opportunities for them equally such [20, 67].

The number of hybrid managers (performing clinical and managerial work meantime) in developed countries is increasing, with the perception that such managers ameliorate the clinical governance of an organization. In contrast, the number of non-clinical managers in many developing countries appears to be increasing [63, 73,74,75]. Included studies suggest this approach does not necessarily amend manager-clinical professional relationships or the willingness of clinicians condign managers, limiting their participation in strategic decisions [28, 70, 71, 74].

Word

This rapid review highlights the electric current global climate in health service management, the key priority areas, and electric current health management approaches beingness utilised to accost these. The multitude of bug emerging demonstrate the complex and evolving role of health service management in the wider circuitous operation of wellness systems globally in a irresolute healthcare landscape. Cardinal themes of achieving high quality intendance and sustainable service commitment were apparent, often evidenced through health reforms [5]. The influence of technological innovation in both its opportunities and complexities is evident worldwide. In the context of changing healthcare goals and commitment approaches, health management is seeking to professionalise as a strategy to build strength and capacity. In doing then, wellness managers are questioning role telescopic and the skills and cognition they need to meet the requirements of the role.

Global challenges facing wellness management

Understanding how the features of the macro, meso and micro systems can create challenges for managers is critical [xix]. With continual healthcare reform and increasing health expenditure equally a proportion of GDP, distinct challenges are facing high-income Organisation for Economic Co-performance and Development (OECD) countries, middle-income rapidly-developing economies, and low-income, resource-limited countries. Reforms, particularly in OECD countries, have been aimed at controlling costs, consolidating hospitals for greater efficiencies, and reconfiguring main healthcare [one, 76]. The irresolute business concern models for the delivery of care accept wider implications for the mode in which wellness managers conceptualise healthcare delivery and the key stakeholders [59], for example, the emerging office of individual healthcare providers and non-wellness actors in public health. Changes to the business model of healthcare delivery also has implications for the distribution of power amongst primal actors within the system. This is evident in the evolved role of full general practitioners (GPs) in the Uk National Wellness Service every bit leaders of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). Commissioning requires a different skill set to clinical work, in terms of assessing financial data, the nature of statutory responsibilities, and the need to engage with a wider stakeholder group across a region to program services [77]. With new responsibilities, GPs accept been required to speedily equip themselves with new management capabilities, reflecting the range of studies included in this review effectually clinician managers and the associated challenges [xviii, 28, 53, 63, seventy, 71, 74, 75].

Central to the role of healthcare managers is the ability to transition between existing and new cultures and practices within healthcare delivery [59]. Bridging this space is particularly important in the context of increasingly personalized and technologically-driven healthcare delivery [54]. While advances in knowledge and medical technologies have increased capability to tackle complex health needs, the integration of innovations into existing healthcare direction practices requires strong change management [73]. Wellness leaders and managers need to be able to rapidly and continually appraise the changes required or upon them, the implications, and to transform their assay into a workable program to realise modify [10]. Focusing merely on the clinical training of wellness professionals rather than incorporating managerial and leadership roles, and specifically, alter direction capability may limit the speed and success of innovation uptake [22].

Implications

Our findings highlight the implications of electric current priorities within the health sector for health management exercise internationally; key issues are efficiency savings, change direction and human resources management. In the context of efficiency approaches, health organisation and service managers are facing instances of poor human and technical resource allocation, creating a disconnect between demand and supply. At the service delivery level, this has intensified and varied the function of center managers mediating at ii master levels. The first level of middle-direction is positioned between the front-line and C-suite management of an organisation. The 2d level of centre-management being the C-suite managers who translate regional and/or national funding decisions and policies into their organisations. Faced with increasing pace of change, and economical and resources constraints, middle managers across both levels are now more than than always exposed to high levels of stress, low morale, and unsustainable working patterns [29]. Emphasis on cost-saving has brought with it increased attending to the wellness services that can be delivered in the community and the social determinants of health. Connecting disparate services in social club to meet efficiency goals is a now a cadre feature of the piece of work of many health managers mediating this process.

Our findings likewise accept implications for the conceptualisation of healthcare direction equally a profession. The scale and increasing breadth of the role of health leaders and managers is evident in the review. Clarifying the professional person identity of 'health manager' may therefore be a disquisitional part of building and maintaining a robust wellness management workforce that can fulfil these diverse roles [59]. Increasing migration of the healthcare workforce and of population, products and services between countries also brings new challenges for healthcare. In response, the notion of transnational competence among healthcare professionals has been identified [78]. Transnational competence progresses cultural competence by considering the interpersonal skills required for engaging with those from diverse cultural and social backgrounds. Thus, transnational competence may be important for wellness managers working across national borders. A fundamental attribute of professionalisation is the educational activity and grooming of wellness managers. Our findings provide a unique and useful theoretical contribution that is globally-focused and multi-level to stimulate new thinking in health direction educators, and for current health leaders and managers. These findings take considerable practical utility for managers and practitioners designing graduate health management programs.

Limitations

Nearly of the studies in the field have focused on the Anglo-American context and health systems. Still the importance of lessons drawn from these health systems, further research is needed in other regions, and in low- and middle-income countries in particular [79]. We acknowledge the nuanced interplay between testify, culture, organisational factors, stakeholder interests, and population health outcomes. Terminologies and definitions to limited global health, management and leadership vary across countries and cultures, creating potential for bias in the interpretation of findings. Nosotros also recognise that there is fluidity in the categorisations, and challenges arising may bridge multiple domains. This review considers challenges facing all types of healthcare managers and thus lacks discrete analysis of senior, centre and front-line managers. That said, managers at unlike levels can acquire from i some other. Senior managers and executives may proceeds an appreciation for the operational challenges that center and front end-line managers may face. Middle and front end-line managers may have a heightened sensation of the more strategic conclusion-making of senior health managers. Whilst the findings indicate consistent challenges and needs for health managers across a range of international contexts, the study does not capture land-specific issues which may take consequences at the local level. Whilst a systematic arroyo was taken to the literature in undertaking this review, relevant textile may have been omitted due to the limits placed on the rapid review of the vast and diverse health direction literature. The inclusion of but materials in English language may have led to further omissions of relevant work.

Conclusion

Wellness managers within both international and national settings confront complex challenges given the shortage of human resource for wellness worldwide and the rapid evolution of national and transnational healthcare systems. This review addresses the lack of studies taking a global perspective of the challenges and emerging needs at macro (international, national and societal), meso (organisational), and micro (individual health manager) levels. Gimmicky challenges of the global health management workforce orient effectually demographic and epidemiological change, efficiency-saving, human resource management, changing structures, intensified management, and shifting roles and expectations. In recognising these challenges, researchers, management educators, and policy makers can found global wellness service direction priorities and raise health leadership and capacities to meet these. Health managers and leaders with adjustable and relevant capabilities are critical to high quality systems of healthcare delivery.

Abbreviations

- CCGs:

-

Clinical Commissioning Groups

- GPs:

-

General practitioners

- HAIs:

-

Hospital acquired infections

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- REA:

-

Rapid bear witness assessment

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Evolution Goals

- UHC:

-

Universal health coverage

- WHO:

-

World Health Arrangement

References

-

Senkubuge F, Modisenyane Chiliad, Bishaw T. Strengthening health systems by health sector reforms. Glob Health Activity. 2014;7(1):23568.

-

World Health Organization, Global Health Workforce Alliance. Human being resource for health: foundation for universal health coverage and the post-2015 development calendar. Report of the Third Global Forum on Man Resources for Health, 2013 November 10–13. Recife, Brazil: WHO; 2014.

-

Reich MR, Harris J, Ikegami Due north, Maeda A, Cashin C, Araujo EC, et al. Moving towards universal health coverage: lessons from 11 country studies. Lancet. 2016;387(10020):811–6.

-

World Wellness Organization. Working together for wellness: the world health report 2006: policy briefs. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2006.

-

Due west M, Dawson J. Employee engagement and NHS performance. London: King's Fund; 2012.

-

World Health Organization. Global strategy on man resources for health: workforce 2030. Geneva: Globe Wellness System; 2016.

-

Reich MR, Javadi D, Ghaffar A. Introduction to the special issue on "effective leadership for wellness systems". Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(3):171–5.

-

Waddington C, Egger D, Travis P, Hawken Fifty, Dovlo D, World Health Organization. Towards better leadership and direction in health: written report of an international consultation on strengthening leadership and management in low-income countries, 29 Jan-1 February. Ghana: Accra; 2007.

-

Globe Health Organization. Quality of intendance: a process for making strategic choices in wellness systems. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2006.

-

Ginter PM, Duncan WJ, Swayne LE. The strategic management of health care organizations: John Wiley & Sons; 2018.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Int Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

-

Grant MJ, Berth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

-

Varker T, Forbes D, Dell L, Weston A, Merlin T, Hodson Due south, et al. Rapid evidence assessment: increasing the transparency of an emerging methodology. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(6):1199–204.

-

Tricco AC, Langlois EV, Straus SE. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health System; 2017.

-

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers G, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A production from the ESRC methods programme Version. 2006;1:b92.

-

Taylor A, Groene O. European hospital managers' perceptions of patient-centred care: a qualitative written report on implementation and context. J Wellness Organ Manag. 2015;29(half dozen):711–28.

-

Costa LBM, Rentes AF, Bertani TM, Mardegan R. Lean healthcare in developing countries: testify from Brazilian hospitals. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2017;32(1).

-

Chreim S, Williams Be, Coller KE. Radical alter in healthcare arrangement: mapping transition between templates, enabling factors, and implementation processes. J Health Organ Manag. 2012;26(2):215–36.

-

Greenwald HP. Direction challenges in British Columbia'southward healthcare system. J Health Organ Manag. 2017;31(4):418–29.

-

Mercer D, Haddon A, Loughlin C. Leading on the edge: the nature of paramedic leadership at the forepart line of care. Health Care Manag Rev. 2018;43(1):12–20.

-

Reijula J, Reijula E, Reijula Chiliad. Healthcare management challenges in ii university hospitals. Int J Healthc Tech Manag. 2016;xv(four):308–25.

-

Srinivasan 5, Chandwani R. HRM innovations in rapid growth contexts: the healthcare sector in Republic of india. Int J Hum Res Manage. 2014;25(ten):1505–25.

-

Afzali HHA, Moss JR, Mahmood MA. Exploring wellness professionals' perspectives on factors affecting Iranian hospital efficiency and suggestions for comeback. Int J Wellness Plann Manag. 2011;26(one):e17–29.

-

Jafari Yard, Rashidian A, Abolhasani F, Mohammad K, Yazdani Due south, Parkerton P, et al. Infinite or no space for managing public hospitals; a qualitative report of hospital autonomy in Islamic republic of iran. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2011;26(iii):e121–e37.

-

Lapão LV, Dussault Thousand. From policy to reality: clinical managers' views of the organizational challenges of main care reform in Portugal. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2012;27(four):295–307.

-

Andreasson J, Eriksson A, Dellve L. Health care managers' views on and approaches to implementing models for improving intendance processes. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(2):219–27.

-

Maluka SO, Hurtig AK, Sebastián MS, Shayo Eastward, Byskov J, Kamuzora P. Decentralization and health care prioritization process in Tanzania: from national rhetoric to local reality. Int J Wellness Plann Manag. 2011;26(2):e102–e20.

-

Taytiwat P, Briggs D, Fraser J, Minichiello V, Cruickshank Chiliad. Lessons from understanding the role of community infirmary manager in Thailand: clinician versus director. Int J Wellness Plann Manag. 2011;26(2):e48–67.

-

Buchanan DA, Parry Eastward, Gascoigne C, Moore C. Are healthcare middle direction jobs extreme jobs? J Health Organ Manag. 2013;27(v):646–64.

-

Longenecker CO, Longenecker PD. Why hospital improvement efforts fail: a view from the front line. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(two):147–57.

-

Reyes DJ, Bekemeier B, Issel LM. Challenges faced past public health Nurs leaders in Hyperturbulent times. Public Health Nurs. 2014;31(4):344–53.

-

Louis CJ, Clark JR, Grey B, Brannon D, Parker 5. Service line construction and decision-maker attention in iii health systems: implications for patient-centered care. Health Care Manag Rev. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000172.

-

Oppel EM, Winter Five, Schreyogg J. Evaluating the link between human resources management decisions and patient satisfaction with quality of care. Health Care Manag Rev. 2017;42(i):53–64.

-

Ramanujam P. Service quality in health intendance organisations: a study of corporate hospitals in Hyderabad. J Health Manag. 2011;13(2):177–202.

-

Diana A, Hollingworth SA, Marks GC. Effects of decentralisation and health system reform on wellness workforce and quality-of-care in Indonesia, 1993–2007. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2015;xxx(1):e16–30.

-

Prenestini A, Lega F. Do senior direction cultures bear upon operation? Evidence from Italian public healthcare organizations. J Healthc Manag. 2013;58(5):336–51.

-

Giauque D. Stress amidst public eye managers dealing with reforms. J Health Organ Manag. 2016;30(8):1259–83.

-

Jennings JC, Landry AY, Hearld LR, Weech-Maldonado R, Snyder SW, Patrician PA. Organizational and environmental factors influencing hospital community orientation. Wellness Care Manag Rev. 2017. https://doi.org/ten.1097/HMR.0000000000000180.

-

Tasi MC, Keswani A, Bozic KJ. Does md leadership touch on hospital quality, operational efficiency, and fiscal performance? Wellness Care Manag Rev. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000173.

-

Hall W, Williams I, Smith N, Gold M, Coast J, Kapiriri Fifty, et al. Past, nowadays and future challenges in wellness intendance priority setting: findings from an international expert survey. J Health Organ Manag. 2018;32(three):444–62.

-

Nelson SA, Azevedo PR, Dias RS, de Sousa SdMA, de Carvalho LDP, Silva ACO, et al. nursing piece of work: challenges for wellness direction in the northeast of Brazil. J Nurs Manag 2013;21(vi):838–849.

-

Ireri S, Walshe Grand, Benson L, Mwanthi MA. A qualitative and quantitative study of medical leadership and management: experiences, competencies, and development needs of doctor managers in the Britain. J Manag Marketing Healthc. 2011;4(ane):xvi–29.

-

Powell M. The snakes and ladders of National Health Service management in England. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2014;29(3):260–79.

-

Groves KS. Examining the bear on of succession management practices on organizational functioning: A national study of U.S. hospitals. Wellness Care Manage Rev. 2017; doi: https://doi.org/x.1097/hmr.0000000000000176.

-

Syed J, Özbilgin M. A relational framework for international transfer of multifariousness management practices. Int J Hum Res Manage. 2009;20(12):2435–53.

-

Adindu A. The demand for constructive direction in African wellness systems. J Wellness Manag. 2013;fifteen(1):1–xiii.

-

Greaves DE. Wellness management/leadership of Modest Isle developing states of the English-speaking Caribbean: a disquisitional review. J Wellness Manag. 2016;eighteen(iv):595–610.

-

Khan MI, Banerji A. Health Intendance Management in India: some problems and challenges. J Wellness Manag. 2014;sixteen(one):133–47.

-

Moghadam MN, Sadeghi V, Parva S. Weaknesses and challenges of master healthcare system in Iran: a review. Int J Wellness Plann Manag. 2012;27(2):e121–e31.

-

Taylor R. The tyranny of size: challenges of health administration in Pacific Island states. Asia Pac J Health Manag. 2016;eleven(iii):65.

-

Jooste Yard, Jasper M. A southward African perspective: electric current position and challenges in wellness care service direction and teaching in nursing. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20(ane):56–64.

-

Sen M, Al-Faisal Westward. Reforms and emerging noncommunicable illness: some challenges facing a conflict-ridden country—the case of the Syrian Arab Republic. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2013;28(3):290–302.

-

Carney M. Challenges in healthcare delivery in an economic downturn, in the Commonwealth of Ireland. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(5):509–xiv.

-

Bowden DE, Smits SJ. Managing in the context of healthcare's escalating engineering and evolving culture. J Health Organ Manag. 2012;26(2):149–57.

-

Meijboom BR, Bakx SJWGC, Westert GP. Continuity in wellness care: lessons from supply chain direction. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2010;25(iv):304–17.

-

Lega F, Calciolari S. Coevolution of patients and hospitals: how changing epidemiology and technological advances create challenges and bulldoze organizational innovation. J Healthc Manag. 2012;57(1):17–34.

-

Kim Y, Kang Grand. The functioning direction arrangement of the Korean healthcare sector: development, challenges, and time to come tasks. Public Perform Manag. 2016;39(ii):297–315.

-

Hernandez SE, Conrad DA, Marcus-Smith MS, Reed P, Watts C. Patient-centered innovation in health intendance organizations: a conceptual framework and case study application. Health Care Manag Rev. 2013;38(ii):166–75.

-

Briggs D, Isouard Grand. The language of health reform and health direction: critical issues in the direction of health systems. Asia Pac J Health Manag. 2016;eleven(3):38.

-

Zuckerman AM. Successful strategic planning for a reformed delivery system. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(iii):168–72.

-

Gantz NR, Sherman R, Jasper M, Choo CG, Herrin-Griffith D, Harris K. Global nurse leader perspectives on health systems and workforce challenges. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20(iv):433–43.

-

Jeurissen P, Duran A, Saltman RB. Uncomfortable realities: the challenge of creating real change in Europe's consolidating hospital sector. BMC Wellness Serv Res. 2016;16(2):168.

-

Kirkpatrick I, Kuhlmann East, Hartley Yard, Dent M, Lega F. Medicine and management in European hospitals: a comparative overview. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;xvi(2):171.

-

Akbulut Y, Esatoglu AE, Yildirim T. Managerial roles of physicians in the Turkish healthcare organisation: current situation and future challenges. J Health Manag. 2010;12(four):539–51.

-

Naranjo-Gil D. The role of top management teams in hospitals facing strategic modify: furnishings on functioning. Int J Healthc Manag. 2015;8(1):34–41.

-

Ford EW, Lowe KB, Silvera GB, Babik D, Huerta TR. Insider versus outsider executive succession: the relationship to infirmary efficiency. Health Care Manag Rev. 2018;43(1):61–8.

-

Leggat SG, Balding C. Achieving organisational competence for clinical leadership: the function of high performance work systems. J Health Organ Manag. 2013;27(3):312–29.

-

Baylina P, Moreira P. Healthcare-associated infections – on developing effective control systems under a renewed healthcare management debate. Int J Healthc Manag. 2012;5(2):74–84.

-

Jha R, Sahay B, Charan P. Healthcare operations direction: a structured literature review. Decis. 2016;43(iii):259–79.

-

Kuhlmann Due east, Rangnitt Y, von Knorring Thou. Medicine and management: looking inside the box of changing infirmary governance. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(ii):159.

-

Spehar I, Frich JC, Kjekshus LE. Clinicians' experiences of becoming a clinical manager: a qualitative written report. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(ane):421.

-

Rodriguez CA. Challenges to effectiveness in public health organizations: the example of the Costa Rican wellness ministry. J Bus Res. 2016;69(9):3859–68.

-

Cinaroglu S. Complexity in healthcare management: why does Drucker describe healthcare organizations equally a double-headed monster? Int J Healthc Manag. 2016;nine(1):xi–7.

-

Rotar A, Botje D, Klazinga N, Lombarts Thousand, Groene O, Sunol R, et al. The involvement of medical doctors in hospital governance and implications for quality direction: a quick scan in 19 and an in depth report in 7 OECD countries. BMC Wellness Serv Res. 2016;16(2):160.

-

Edmonstone JD. Whither the elephant?: the continuing evolution of clinical leadership in the United kingdom National Health Services. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2014;29(iii):280–91.

-

Naylor C, Ross S, Curry N, Holder H, Marshall L, Tait E. Clinical commissioning groups: supporting improvement in general practise? London: The Rex's Fund; 2013.

-

Holder H, Robertson R, Ross S, Bennett 50, Gosling J, Curry N. Take chances or reward? The changing function of CCGs in general practice. London: Kings Fund/Nuffield Trust; 2015.

-

Koehn PH, Rosenau JN. Transnational competence in an emergent epoch. Int Stud Perspect. 2002;3(2):105–27.

-

Antunes 5, Moreira JP. Skill mix in healthcare: an international update for the direction debate. Int J Healthc Manag. 2013;6(1):12–7.

-

Seitio-Kgokgwe OS, Gauld R, Hill PC, Barnett P. Understanding human resource management practices in Republic of botswana's public health sector. J Wellness Organ Manag. 2016;30(viii):1284–300.

-

Miners C, Hundert M, Lash R. New structures for challenges in healthcare management. Healthc Manage Forum. 2015;28(3):114–7.

-

Hopkins J, Fassiotto Yard, Ku MC, Mammo D, Valantine H. Designing a md leadership evolution program based on effective models of md education. Health Intendance Manag Rev. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/hmr.0000000000000146.

-

Miranda R, Glenn SW, Leighton JA, Pasha SF, Gurudu SR, Teaford HG, et al. Using hybrid change strategies to improve the patient experience in outpatient specialty intendance. J Healthc Manag. 2015;60(v):363–76.

Acknowledgements

Non applicable

Funding

The rapid review is part of a larger study on global health management priorities and qualities, supported by the Academy of New S Wales, Sydney.

Availability of data and materials

The data that back up the findings of this review are included in this published article.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

CF conducted the database searches and identification of relevant literature. RH and AC assessed the selected literature. RH and LM conceived the design of the review and contributed to the interpretation of the review results. CF drafted the initial manuscript while RH, AC and LM reviewed and revised subsequent drafts of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Non applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher'southward Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and betoken if changes were fabricated. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the information made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Figueroa, C.A., Harrison, R., Chauhan, A. et al. Priorities and challenges for health leadership and workforce management globally: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv Res 19, 239 (2019). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12913-019-4080-7

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12913-019-4080-7

Keywords

- Health service management

- Health leadership

- Workforce

- Global health

- Challenges

- Priorities

Source: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-019-4080-7

0 Response to "in order to compare and contrast leadership perspectives across the globe what constructs were used"

Post a Comment